Image from Allegany Art

WHY WE DO WHAT WE DO

An introduction to Psychodrama, sociodrama and sociometry

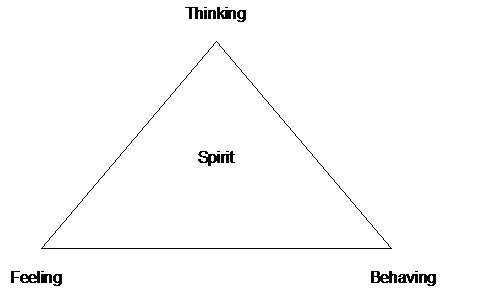

One means of our creating a container by which we can briefly examine psychodrama theory would be by looking at the relationship that exists between our Thinking/Feelings/Bodies & Behaviors. In the center is Spirit, a concept that is perhaps more obvious in the creative arts therapies than in other disciplines. This validation of our spiritual dimension was essential to J.L. Moreno, the father of Psychodrama.

This introductory workshop is designed to welcome you and help you feel more comfortable with subsequent workshops at this conference.

Together we will examine an overview of psychodrama, sociometry and group psychotherapy. We will demonstrate ways to use action methods to achieve and maintain appropriate and healthy equilibrium between our cognitive, emotional, physical/behavioral and spiritual responses. When each of these aspects are present, we can better access deeper aspects of our humanity. This article offers an understanding of several basic terms, tools, and techniques that are a part of psychodrama.

You will notice how often an area sub-divides into three related aspects of the one whole. In a psychodrama session, the psychodramatist continually works to balance these triune aspects. This balance becomes a means for helping group members achieve a deepened consciousness and connection with themselves and with the community around them. First, we will identify the resources necessary for a psychodrama.

THE FIVE KEY INSTRUMENTS FOR THE PSYCHODRAMA:

J.L. Moreno identified 5 key instruments necessary for a psychodrama. This information is found in Moreno’s article on Psychodrama and Sociometry in Psychodrama Volume I.

The Stage

- This provides the arena for the action to occur. This setting can be either a real location or a fantasy world. The stage provides safety to all the participants through containment. In addition, creating the setting offers freedom by becoming a place where fantasy and reality can co-exist.

The Protagonist

- This is the person who is telling his or her story. Unlike an actor, who speaks from a defined script, the protagonists in psychodrama and sociodrama are allowed the spontaneity necessary to tell and develop their dramas in the moment, through thoughts, emotions and actions.

The Auxiliary Egos

- Psychodrama values interaction between group members as key to healing both the protagonist and the other participants in the group. Since our hurts and injuries occur within the context of relationships, the reparative work is most effective when it occurs within relationships, in this case, the group setting. Auxiliary egos are played by group members, who take the part of significant others in the drama. Auxiliaries might also have the roles of disowned or wounded parts of the self. At times, the auxiliaries can represent concrete objects (a chair, a bottle, an ocean) that have significance within the drama.

The Director

- The director acts as producer, counselor and analyst. She or he maintains contact with the protagonist, and facilitates the immediate action of the drama, and facilitates transitions to other scenes. Through the tools of psychodrama, the director can lead the psychodrama into insight or help participants interpret the action. At the same time, the director will observe, monitor or intervene with others in the group as necessary.

The Group or the audience

- The group members offer support and containment for the protagonist. They provide an anchor throughout the warm-up and action. They are the collective from which the protagonist can choose auxiliaries. Through sharing they also assist the protagonist in cooling down at the end of the enactment. As psychodrama is primarily a method of group therapy, the members also have a commitment to use the drama to identify and speak to their common ground of shared issues. Perhaps, the more accurate term for these individuals is ‘witnesses’.

THREE BRANCHES OF PSYCHODRAMA:

Within the discipline of psychodrama, there are three distinct branches. While these branches can overlap within a psychodrama session, it may be worthwhile exploring the contribution of each of them individually.

Sociometry

- The measurement of social/relational choices, focused on specific criteria. Sociometry helps to identify and clarify the underpinnings of a group, in terms of the cohesion or lack of connection that affect participants. It can be used as a warm-up or to clarify the group’s dynamics. Sociometry can be measured through observations, in action, or through various pencil and paper sociometric tests. Preferred criteria are non-judgmental and are criteria that can be acted upon. Additionally, criteria are chosen which focus or reflect the group’s dynamics. Some forms of sociometry include spectrograms [measuring ambivalence or graduated reactions to the criterion] locograms ([using space or location to determine choices or interests) and action sociograms (choices between individuals, made in action among the full group membership) Moreno felt this was his most important contribution to the world. He told colleagues that he brought people in through psychodrama and healed them through sociometry.

Sociodrama

- An enactment in which a situation is explored through the focus of a single major role relationship. Sociodrama deals with the collective roles of a group or culture, and maintains the focus on this shared aspect, rather than on particular individuals. It is the “group’s drama”, rather than limited to one specific person. As such, roles can be fluid, rather than remaining with one individual.

Psychodrama

- The word psyche refers to the mind or mental life of the person. Drama, means action or a thing done. Psychodrama is the science that explores the human experience through dramatic action. In contrasting the different branches, a ‘traditional’ psychodrama would focus on a particular protagonist, and his or her story, as it is enacted within the session.

THREE PARTS OF A PSYCHODRAMA SESSION:

Each individual session would include three specific parts. These three parts works in sequence to facilitate the group in creating a healing moment for all participants.

Warm-Up:

- The warm-up occurs at the beginning of a session. This is an opportunity for the members to become familiar with one another and the space. During this time, the director listens as individuals share, seeking out common ground and the developing energy within the session. At other times, the director might choose to bring in a structured warm-up-an exercise or action structure that will help members to focus on particular issues or themes. Moreno did not believe in resistance. Rather he felt this indicated that the protagonist or group were not sufficiently warmed up.

Enactment:

- The enactment is the part of the session in which the protagonist is chosen, and the drama begins to develop. In some ways it is a continuation of warm-up as the protagonist and director develop a contract and goals for the psychodrama. During the enactment, the protagonist chooses certain group members to become auxiliary egos. The director will employ various means to help warm up the auxiliary egos to their roles, and to facilitate the action as it occurs. In a drama, it is important to note that the principles of warm-up continue to be respected. A drama begins at the periphery and moves towards the core of the matter, as the protagonist and auxiliary egos warm up to their roles, to each other, and to the issue at hand.

Sharing:

- The last phase of a psychodrama is the sharing. Following the enactment, the protagonist rejoins the group, and members share with the protagonist how the drama has affected them, particularly how parts of their own story parallel the drama. It is important to keep the group at a sharing level, rather than processing or interpreting the drama. This maintains the drama as a group modality, and allows both the protagonist and the auxiliaries to reestablish their identity as members of this group. The sharing is also a time, when auxiliary egos will de-role from the drama, both through their sharing, and through the facilitation of the director. (In a training group, members may process a drama after the sharing is completed, as this experience also becomes a part of their learning.)

THREE LEVELS OF A PSYCHODRAMA:

Psychodramas can occur on three levels. Typically, one level is dominant; however each level will frequently be represented in the psychodrama. One task of the director is to help the protagonist identify the appropriate level for the current need, and then maintain the contract in the drama. Attention to these dynamics prevents the drama from becoming too convoluted, or blurring these levels in a manner that defeats the goals of the protagonist.

Intrapsychic

- These are dramas that focus on the internal parts of ourselves. Such a drama might include accessing some of our inner strengths or in claiming parts of ourselves that we have disowned. They might involve confronting our shame or anger, and letting go of destructive emotional baggage. The intrapsychic dramas frequently look at shifting and re-integrating our internal structures in a manner that allows us more freedom and spontaneity.

Interpersonal

- These are dramas focusing on our relationships with others. Interpersonal dramas can involve relationships from the past, current relationships or future projections and those potential relationships which are ahead of us. Some of the goals of interpersonal dramas might include healing past wounds caused by our own behavior or by others. We might want to develop greater empathy, or to view a childhood relationship thought the eyes of an adult, to gain insight that we couldn’t achieve when we were younger. JL Moreno believed the smallest human unit was 2 or more. Therefore, Interpersonal dramas tend to have more lasting impact as we move through our world. One useful tool for exploring an individual’s social world is through their Social Atom.

Transpersonal

- These are the dramas that move beyond the individual, and include encounters with our higher self, God as we understand God, or our Greater Truth. These dramas can occur when someone is focused on an issue much deeper than the immediate presenting problem, and can typically emerge out of psychodramas involving grief work, healing childhood traumas, HIV/AIDS work, forgiveness, spiritual and religious issues, or addiction and recovery themes.

THREE TIME FRAMES OF A PSYCHODRAMA:

When a drama is enacted, the action always occurs in the present moment. It is important to keep the protagonist dealing with the situations as they are, not describing them as they were or as they might be. Nonetheless, the scenes of the drama can emerge from any of three time periods.

Past

- These dramas can allow the protagonist to return to a scene of safety or comfort - to anchor a time of positive feelings. Alternatively, the dramas may focus on hurts or difficulties that occurred in the past. By bringing the action into the here-and-now, the protagonist is freed to deal with their current feelings and to access current resources which might not have been available during the original situation. The director transports the past scene into the present moment, which can allow the protagonist to bring spontaneity to the situation, rather than simply having a person replaying a familiar but stale script. It is important that dramas do not re-traumatize an individual but focus on healing from these past wounds.

Present

- Dramas that occur in the present address the protagonist’s immediate emotional response regarding events in their life: home, employment or relationships. They may address interpersonal issues within the psychodrama group. Psychodramas involving actual individuals rather than auxiliaries are referred to as an encounter. In any psychodrama, these issues are viewed not simply as involving two individuals, but also being a reflection of and impacting on the person’s larger social world or the group as a whole. Therefore, through action, the group becomes a resource for resolving these conflicts. Likewise, sociodramas frequently address issues in the group as a whole, paralleling the present moment.

Future

- In psychodrama, we might enact a future projection. This allows a person to move forward to a time or event yet to be, and to explore the dynamics involved. Future projections can often be used as a vehicle for role training a protagonist, thereby allowing them to identify potential obstacles and to become more familiar and comfortable with the new, desired behavior.

THREE GOALS OF A PSYCHODRAMA:

Within the context of any psychodrama, there are three goals. When negotiating the contract between a protagonist and director, one or more of these goals will be identified and addressed. These goals include:

Insight:

- Through psychodrama, we can reach a new understating of ourselves, our environment, or the patterns we play out in our daily lives. Insights can be Spiritual, cognitive, emotional, or somatic (body/action centered)

Catharsis:

- Moreno made an important distinction regarding catharsis. There is the common understanding of catharsis as a release of pent- up or previously blocked emotion. A catharsis can include anger, tears or laughter. Often the catharsis of laughter is underrated, yet can be an important aspect of our healing journey. He referred to this as a catharsis of abreaction. More important is the catharsis of integration. This is the point when we restructure and reintegrate our experience in a new and healthier manner.

Role Training and Development:

- Action methods offer the ability to develop and practice new behaviors in situ, to test these behaviors out, and become more comfortable with new roles while working within the safety of the group. By actively practicing new behaviors, we develop through the three stages of role development:

- role taking

- role playing

- role creating

We move from initially observing modeled behavior in others and imitating their behaviors, through a period of exploring variations of particular behaviors as they are more effective or satisfying to integrating it within ourselves, each level exhibiting an increased spontaneity.

In working to meet the contracted goals of the psychodrama the director will utilize a number of tools and techniques. Several of these can be used to advantage with any of these points on the pyramid; some are particularly useful in accessing a specific perspective.

TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES

Doubling

- In doubling, an auxiliary ego, positions himself or herself to the side and slightly behind the protagonist. The double will usually take on the physical position of the protagonist, and is there to give voice to the underlying or unspoken thoughts, feelings or responses. Most commonly, the double is used to help deepen affect. However, well used, a double can also be used to expand the variety of feelings being experienced. For instance, a double might bring anger in to a scene in which the protagonist is primarily aware of sadness, so that both feelings can be validated. However, a double can also be used to increase the cognitive aspects of a drama. This can be particularly useful when an individual is ‘overheated’ in a drama, and needs to be grounded. Doubles often provide the protagonist with increased feelings of safety, which is of critical importance when working with survivors of trauma. Doubles can also augment somatic experiences, allowing the protagonist to become increasingly aware of his or her physical responses within the scene.

Mirroring

- A mirror is a technique in which the director has an auxiliary ego temporarily assume the role of the protagonist within the drama. The protagonist is then allowed to step out of the scene, and view it from a distance. The mirror frequently is very useful in accessing cognitive awareness, as the technique tends to increase the objectivity with which the protagonist views the scene. Mirrors can nonetheless also help access feelings, particularly when the scene is intense. They can provide safety, when the protagonist begins to shut down emotionally. Mirroring is a valuable tool when working with sensitive themes, as a means of lowering the likelihood that a protagonist will be re-traumatized by events occurring within a drama.

Soliloquy

- Often spoken of as the ‘walk-and-talk’, the soliloquy is most commonly used at the beginning of the drama. The protagonist walks with the director, allowing the director, the protagonist and the group to warm up to the themes of the drama. It is during this time that the protagonist will speak about his or her warm up, the issues to be addressed, and possibly begin to identify scenes or auxiliary egos for the drama. The director will use the soliloquy to establish their contract, or the expected goals and directions that the drama will take. Soliloquies can also occur during the drama, to give the protagonist a ‘time out’ to process the events.

Aside

- An aside is a moment within the drama, in which the protagonist is able to identify an immediate thought or reaction, without other auxiliaries responding to it. Asides can surface additional information or affect that might be underlying an interaction or which is too frightening or upsetting to say out loud. Generally in an aside, the protagonist will turn her or his head, and make the internal statement to the director/group members, and then return to the action of the drama, but with this additional information now available for therapeutic intervention.

Concretization

- This is a tool for shifting an issue from a generality to a specific, or for intensifying metaphoric language by focusing it in a physical action. Having someone/something represent the burden the protagonist is carrying would be an example of concretization. Often concretizations help to access the physical aspects of a person’s experience, and make the drama more incarnate.

Interviewing

- When an auxiliary is chosen, it is the director’s responsibility to elicit the information that individual needs to accurately portray their auxiliary role. This is a specific use of the role reversal, in which the protagonist expresses attitudes, mannerisms, phrases, etc. that will be important within the drama. Particularly in a group with minimal history together, do not assume the auxiliaries will be able to ‘wing it’.

There are many other tools and techniques available to the trained director for balancing thinking/feeling/physical and behavioral elements of a drama. These choices determine what will best serve the protagonist and the group during a specific psychodrama session.

In each of the categories discussed above, the director will assess and determine the dominance of a particular aspect of the drama – will it be primarily a drama in the present, from the past or a future projection? What will effectively meet the goals and objectives identified during the warm up and the contract between the protagonist and the director? Psychodramas can expand rapidly and intensely.

Zerka Moreno noted a psychodrama can be a means of restraint as well as a means of expression. There are situations in which the client needs to practice and reinforce boundaries and containment rather than cathartic expression of emotion. Often, in working with trauma, the early dramas are focused on building resources. Clients can want to create a scene of confrontation with an abuser. However, these can have potential to actually retraumatize an individual when done prematurely. Often the healing occurs through dramas of integration, where there is not a need to revisit a traumatic episode. Because psychodrama can be such a powerful tool, it is critical that the practitioner understands those tools and techniques that promote and maintain safety for the protagonist, the auxiliaries, and the entire group.

It can be helpful to consider the Window of Tolerance in developing and directing a psychodrama. Although the group might have an act hunger to experience an intense drama, the clinician willrecognize that the therapeutic work happens within that window, both for the protagonist and for the others in the group.

In seeking competent clinical or supervisory psychodramatic services, a client or clinician ought to be aware of the credentialing process involved in certification within this field.

THREE LEVELS OF CERTIFICATION:

Certification is granted through a national certifying body, the American Board of Examiners in Psychodrama, Sociometry and Group Psychotherapy. The ABE is a separate and distinct group from the ASGPP [American Society of Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama], which is the membership organization. The requirements of certification at each level is available on their website.

The American Board of Examiners can be reached through:

American Board of Examiners

1629 K Street NW

Suite 300

Washington DC 20006

www.psychodramacertification.org

202-483-0514

Certified Practitioner: CP

- This level designated individuals who have met the required education and subsequent ABE approved psychodrama training, and supervision, and who have passed both a written examination and on-site observation.

Practitioner Applicant for Trainer: PAT

- These individuals have already received their CP certification, and have formally been accepted into training to become certified trainers. Individuals seeking CP level certification can receive up to 160 training hours from an approved PAT.

Trainer, Educator, Practitioner: TEP

- These individuals have completed their PAT process, and have passed both a written and on-site examination with the Board of Examiners. They are approved to provide supervision and training in psychodrama to all CP candidates.

The website for the American Association of Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama is www.ASGPP.org. This will give access to information about the field, links to regional collectives, and some articles and books in their library section.

A FEW FINAL THOUGHTS:

Moreno developed his theories by observing children playing in the park. He began to apply these with marginalized groups. Psychodrama therefore has a history of supporting inclusion and celebrating diversity.

Social Atom is a means of exploring an individual’s social/relational world. It can be used as part of a client’s intake, as a way of identifying desired areas of change and as a means for identifying an individual’s resources. A Social Atom maps an individual's relationships. It can be used to identify interpersonal resources. It can be the basis for identifying potential dramas. You can find an article on developing a person’ social atom at www.dreamer2doer.com

Stephen F Kopp, MS, CAS, TEP

© copyright March 2007

Revised April 2024