JOURNEY TO OZ - Dare to Dream Again

ASGPP National Conference,

April 5, 2024

Los Angeles California

Somewhere over the rainbow, skies are blue And the dreams that we dare to dream really do come true. Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg

Someday we'll find it the rainbow connection the lovers, the dreamers and me…“The Rainbow Connection” from: The Muppet Movie, 1979 Paul Williams and Kenneth Ascher

“You analyze their dreams. I try to give them the courage to dream again.” JL Moreno to Freud, 1912

The image that somewhere over the rainbow, dreams really do come true is a powerful one. To have rainbows, we need both sunlight and rain. Often the realization of a dream includes exploring our shadow side as well as celebrating our light. This courage to dream is an integral aspect of psychodrama. Beyond their specific problem, our clients are often seeking a pathway back to their dream. In dreams, we need not be limited by time, space, gravity. Psychodrama serves as a powerful tool for returning to, revising or recreating our dreams.

There are many things that can obscure or block our dreams: mood disorders such as depression or anxiety, or somatic issues involving serious illness or chronic pain. Our dreams can be shadowed by trauma, by financial or physical concerns. We might put aside our dreams to we carry responsibilities or care-taking someone else. Most damaging are those blocks, initially external, that we have repeated and repeated to ourselves, internalized, and now carry into our daily activities.

We are not born into this world with these internalized blocks. Moreno developed his theories of spontaneity and creativity through observing children playing in the parks in Vienna. Elizabeth Bergner wrote about Moreno’s engaging play: “But you don’t need a skipping rope for skipping! Come, let’s give the skipping rope to a poor child who never had one! But you don’t need a ball to play ball! Come, I’ll toss the sun to you, catch it!” Marineau, pg 36

I was not looking for my dreams to interpret my life, but rather for my life to interpret my dreams. Susan Sontag

We can see common threads between our dreams and the structure of psychodrama. We are not analyzing or interpreting our dream, but experiencing it in action. Moreno chose to use our whole bodies and not be limited to a verbal narrative. Rather than having participants focus their attention and energy on the therapist or group facilitator, he encouraged direct interaction among peers. His concept of surplus reality speaks to a vision that allows space and respect for our dreams.

Moreno understood “the body remembers what the mind forgets.” This can be observed from something as simple as touch typing or driving a stick shift to something as complex as holding somatic memories of trauma. Therefore, experiential methods offer a primary tool for identifying and understanding those blocks that inhibit the fulfillment of our dream.

In Kansas, Dorothy wonders if such a place exists, where dreams really do come true. Once she travels over the rainbow, each of the friends she meets in her journey has a dream. What is significant is that each person already embodies their dream in their actions. In the movie, the Scarecrow comes up with an idea for getting apples from the talking trees. In the book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the Scarecrow develops a plan for crossing a wide river, and has a strategy for escaping the Kalidahs, savage beasts they encounter on their way to the Emerald City. (Chapter 7) The Tin Man has enough compassion to weep when he steps on a beetle. (Chapter 6) The Lion intimidates the Kalidahs until the others escape. Even Dorothy has the power to return home as soon as she puts on the magic slippers. Therefore, their problem is not that their dreams are unrealistic, but that internal blocks prevent each person from recognizing the dream in its process of becoming. The Wizard offers the companions an object to concretize what they already possess. Instead of mere words, he offers them a tangible object or action to strengthen their process of acceptance. In the book the Wizard offers the Lion, not a medal but a bowl of liquid. When he is asked what it is, the Wizard says that he doesn’t know. He tells the Lion that if it was inside, it would be courage, as courage always comes from within. And the Lion quickly drinks it all up. The action of physically taking in the liquid helps to anchor his cognitive belief that he is now full of courage.

In the book, they continue to travel south to fulfill Dorothy’s dream. And through their increased recognition and acceptance of their gifts, they can now overtly engage their strengths in their journey.

The Wizard, as we know, is a humbug. His misdirected dreams of remaining in power lead him to disguise his natural human form. In the book, he appears differently for each person: to Dorothy the disembodied, thundering head, to the Scarecrow as a beautiful winged maiden. The Tin Man encounters a great beast. And the Lion is faced with a ball of fire. As long as the Wizard maintains his toxic dream of power, he remains isolated. Paradoxically, he is actually the prisoner, not the ruler of the palace and the Emerald City. Our true selves and true dreams can also be masked. Our false images might be negative introjects from our family of origin, and subsequent mistrust of self. We might be blocked by a history of trauma. Our dreams may be hidden among fears, whether of disappointing someone, or even of excelling over someone. We can surrender our dream in care-taking or codependent relationships. Depression and anxiety can shadow our dreams.

Once we embrace the courage to dream again, there are several doorways into our dream. The Wizard presented each person with a tangible expression of their dream; psychodrama offers ways to concretize our experience of overcoming obstacles and achieving our dream. We will look at the application of some of these tools in this workshop.

Dreams say what they mean, but they don’t say it in daytime language. Gail Godwin

This workshop follows the yellow brick road of Oz –a story of the archetypal journey. Certainly, psychodrama commonly uses stories and metaphors to offer insight into our difficulties and solutions and allows us to journey into our dream.

In understanding our blocks, we are not limited to our narrative story, but also access non-verbal possibilities. This can include physical positioning, using movement and sound to express the block to our dream. Family sculpting, empty chair and role reversals can be additional ways to clarify what is inhibiting our dream. For block involves trauma, we can maintain safety and boundaries by working from a Playback Theater or mirror position. This can offer a safe, yet visceral way to bring in fresh perspectives and elicit group empathy and support.

We need to not only recognize our blocks, but honor and appreciate our possibilities so our dreams really do come true. There are many tools within psychodrama for stepping closer and into our dream. We can use objects or auxiliaries to give a voice to the dream. A wonderful tool for reawakening the dreamer is the future projection. This allows the protagonist to experience achieving their specific dream. You can create a time line for the protagonist: working backward from the dream to identify a series of doable steps. This breaks the dream into manageable stages, ending with the full realization of the dream.

Invite a protagonist to role reverse with a strength or resource, with his or her wise mind, or the higher self. Mirroring can also be effective in strengthening our resources. Making resources concrete will offer a different perspective and help expand awareness. The protagonist might then perceive potential new ways to utilize resources already in his or her possession to fulfill his or her dream. This pattern of gaining momentum into one’s potential is evident throughout the journey to the Emerald City.

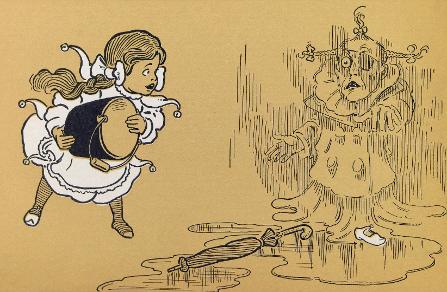

Part of the magic of psychodrama rises from a belief that our dreams likely hold more energy than the darkness. This is why JL Moreno was less interested in analyzing dreams than in validating them. Whatever power the wicked witches have, they are stopped in fairly simple ways: whether by standing in the wrong place at the wrong time or being soaked by a bucket of water. In the book, Dorothy continues journeying south after the Wizard prematurely leaves in his balloon. When the companions finally encounter Glinda, each receives dreams beyond their expectations: The Scarecrow returns to Emerald City to become their ruler. The Tin Man has been asked by the Winkies to rule them from the castle of the Witch of the West, now that she is ‘liquidated’. And after having his courage validated by the Wizard, the Lion saves the animals of a great southern forest from a hideous monster. The Lion accepts their request to return to be their king. Even the flying monkeys achieve their freedom. As a result of her journey, Dorothy’s dream also expands. In the opening chapter, Aunt Em has been faded gray by the Kansas prairie, to the point she is startled whenever Dorothy laughs. In the final chapter, Dorothy’s reunion with Aunt Em is greater than Dorothy’s initial dream to go home:

“My darling child!” she cried, folding the little girl in her arms and covering her face with kisses; “where in the world did you come from?”

My hope is that this workshop invites each of you to dare to dream and to celebrate as your dreams really do come true.

Steve Kopp

"Reminding one another of the dream that each of us aspires to may be enough for us to set each other free." -- Antoine de Saint-Exupery, poet and pilot

Baum, L Frank, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Dover Publications, New York 1996

Marineau, Rene, Jacob Levy Moreno 1889-1974 Tavistock/Routledge, London & New York 1989